There’s been quite a bit of buzz about bees lately. Two weeks ago, the White House released a Presidential Memorandum establishing a “Pollinator Health Task Force” with plans to improve pollinator health and habitat. Many people (including the Pollinator Team at Center for Food Safety) were pleased to hear the White House acknowledge the impact of pesticides, especially neonicotinoids (“neonics” for short). Acknowledgment of the problem is the first step toward recovery, but as we’ve said before, simply acknowledging these impacts will not improve current pollinator declines – we need immediate action.

We have a long way to go to deal with the ramifications of these pernicious chemicals. As we forge ahead with new policy and regulatory initiatives, it’s important that we first understand how we got into this toxic mess in the first place.

Click to enlarge

EPA and Neonicotinoids: A Bumbling Affair

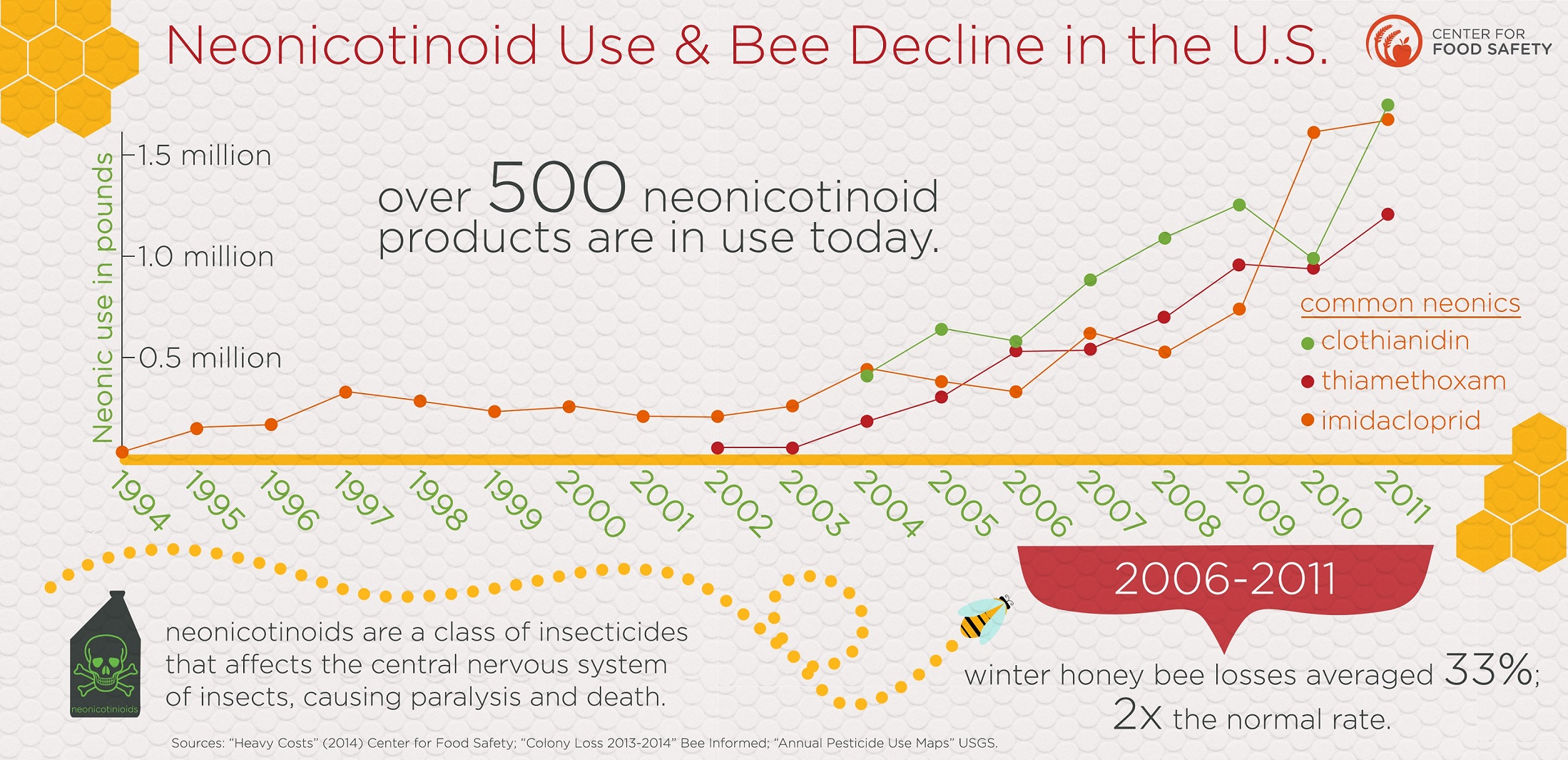

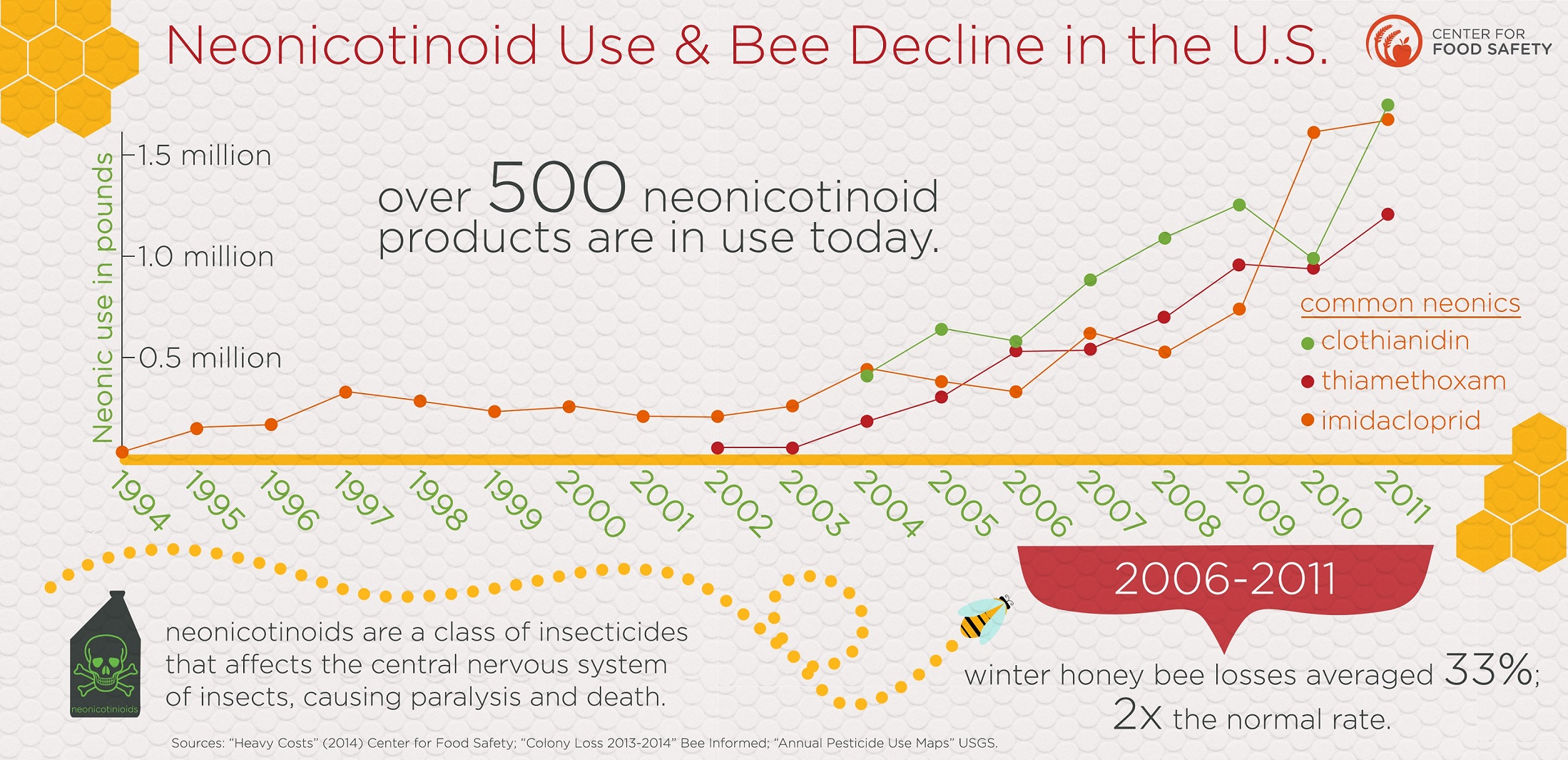

Neonics are a relatively new class of insecticides, modeled after nicotine, which interferee with the nervous system of insects, causing tremors, paralysis and eventually death at very low doses. In 1994, the EPA approved the first neonicotinoid chemical (imidacloprid) for limited use on ornamental plants and turfgrass. In the 2000s, EPA began approving more neonics like thiamethoxam (2000), acetamiprid (2002), clothianidin and thiacloprid (2003), and dinotefuran (2004). The approval of these new pesticides was controversial. In scientific assessments and early reviews dating back to 1993, EPA scientists had serious concerns with the high toxicity of these chemicals to honey bees, birds, and other wildlife, as well as to endangered species. Yet EPA’s decision makers overruled the scientists and downplayed their warnings.

It is important to point out that even though the first neonicotinoid was approved for limited use in 1994, it was not until the mid to late 2000s that these chemicals were used extensively throughout the United States. Neonics are now the most widely used insecticides in the world, with over 500 different neonicotinoid products on the market, and applications estimated to exceed 150 million acres annually nationwide. Neonics are sprayed on a huge variety of crops, trees, and turfs, but one of their largest uses is as a seed treatment on most annual field crops (such as corn, soybeans, wheat, canola, and cotton). Neonics are more persistent in soil and water than most other insecticides and have the ability to accumulate in the environment. Neonicotinoids are also very mobile and have been detected frequently in water bodies next to agricultural areas where they are used. Neonicotinoids are “systemic” and move into the plant tissues, contaminating its fruit, pollen and nectar.

Most importantly, neonics are one of the most toxic classes of chemicals to bees and will kill bees and other beneficial insects at nanogram levels.

Pollinators in Peril

In the mid-2000’s, severe colony losses started to raise serious concerns for beekeepers. Viruses and pests have always been a problem, but for decades beekeepers had been able to keep bee colony losses to 10-15%. In the early to mid-2000s – around the same time neonicotinoids gained a large share of the insecticide market – this all changed. Beekeepers began witnessing winter losses of around 33% and annual losses of 50-60%. Beekeepers reported bees dying right in front of their hives. Bees were also becoming disoriented, unable to navigate effectively, and disappearing from the hive.

The phenomenon was named “Colony Collapse Disorder” (CCD) and Congress held hearings in 2007. Congress also allocated research funding to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and tasked them with discovering the cause of CCD. In one of those 2007 hearings, USDA’s Agricultural Research Service Associate Administrator Caird Rexroad testified that USDA considered pesticides to be one of the top stresses on bees because they suppress their immune systems, causing them to become more susceptible to disease and pests. Numerous peer-reviewed studies have since established that to be the case. Yet despite this testimony, the overwhelming majority of the money that Congress appropriated was spent on factors other than pesticides. The limited pesticide research that was conducted was not even rigorous enough to be incorporated into EPA’s pesticide risk assessments, rendering it near useless.

Seven years and millions of taxpayer dollars later, government agencies have yet to identify the cause of the “mysterious” bee disappearances and die-offs. They have instead shifted focus to improving bee health, citing multiple factors associated with the bee losses. Yet independent scientific research has continued. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) expert Task Force on Systemic Insecticides recently reviewed over 800 peer-reviewed published journal articles from the past two decades. The scientists determined that neonics are accumulating in soils and polluting waterways and natural vegetation across the world, leading to widespread impacts on wildlife. The Task Force also articulated that growing evidence indicates much of their use is unnecessary and ineffective. Due to a number of concerning factors surrounding the use of systemic pesticides (namely their prophylactic use, persistence, mobility, systemic properties and chronic toxicity), the Task Force has predicted potentially devastating, even irreversible, impacts on pollinators and other beneficial species, biodiversity. That is, unless we do something to save the bees.

Bee Aggressive!

We at Center for Food Safety believe 100 percent that pollinators are essential to a healthy food supply and environment. Right now, the current losses are unsustainable. It is urgent that our regulatory agencies take more aggressive action to prevent further declines of pollinator species, and acknowledge the role that pesticides play. The latest White House task force offers some hope of a new, more assertive direction, and not a moment too soon.